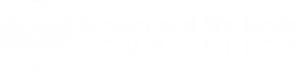

Before European settlement, the Bloody Run Swamp wetland and stream mitigation site was part of an approximately 450-acre wetland, later to be called the Bloody Run Swamp. It was the second largest wetland in the area after the Great Swamp, which eventually became Buckeye Lake (Figure 1). Indigenous Americans traveled and hunted in this area following buffalo paths and “Old Hebron Road,” which offered easy passage between Bloody Run Swamp, Bloody Run and the South Fork Licking River. It also led to Flint Ridge, in the eastern part of the county, where they collected material for flints.

This part of Ohio was largely un-touched by European settlers prior to 1800. The first European cabin in the area was likely built between Bloody Run and the present-day Village of Kirkersville in the early 1800’s. Etna township was settled in 1815, and over the next fifteen years, the large influx of citizens made it necessary to set up their own local government. In 1805, the United States Congress passed an act allowing the construction of a major road that would facilitate travel from Cumberland, Maryland, to Ohio. This road, National Road (U.S Route 40), reached Columbus in 1825, and hastened human expansion in its path. The building of the National Road was, “the most important event in the life of Kirkersville and Etna Township,” and its importance and influence on shaping Ohio’s early life cannot be overstated (Schaff, 1905).

Impacts to the Great Swamp

Between 1825 and 1828, the Great Swamp was drastically impacted by the building of the Ohio canal system. The “old reservoir,” which was later named Buckeye Lake in 1894, was built, which effectively drained the Great Swamp. The water level in this reservoir was not high enough to feed the canal in the summer, so a second 500-acre reservoir was constructed in 1832. Creeks and small streams, including portions of Bloody Run, were straightened into feeder canals, shown on Figure 2, which were diverted to the reservoir for use in the Ohio canal (Detmers, 1912). Increases in settlement, the National Road, canals, and reservoirs led to the removal of forests and drastic topographic modifications. By 1840, the Bloody Run Swamp was the only regional wetland that remained in its primitive or “primeval” state (Trautman, 1939).

A man named Morris Schaff grew up in this area in the mid-1800’s and wrote Etna and Kirkersville, in 1905. He described the local families, conditions of daily life, and dedicated significant portions of this book to descriptions of the plant and animal life in and around the Bloody Run Swamp. These descriptions give a first-person account of what the Bloody Run Swamp was like before being completely drained and cultivated for agricultural use. He wrote:

“The head of this swamp, now practically all cleared fields, when I was a boy was about a half mile east of Kirkersville and reached to the old bed of Licking Creek, a distance of two and a half miles. It was about a half mile wide and was a thickly matted growth of willows, young elms, water beeches and alders. In the middle were several islands covered with big timber where the last of the wild turkeys roosted” (Schaff, 1905).

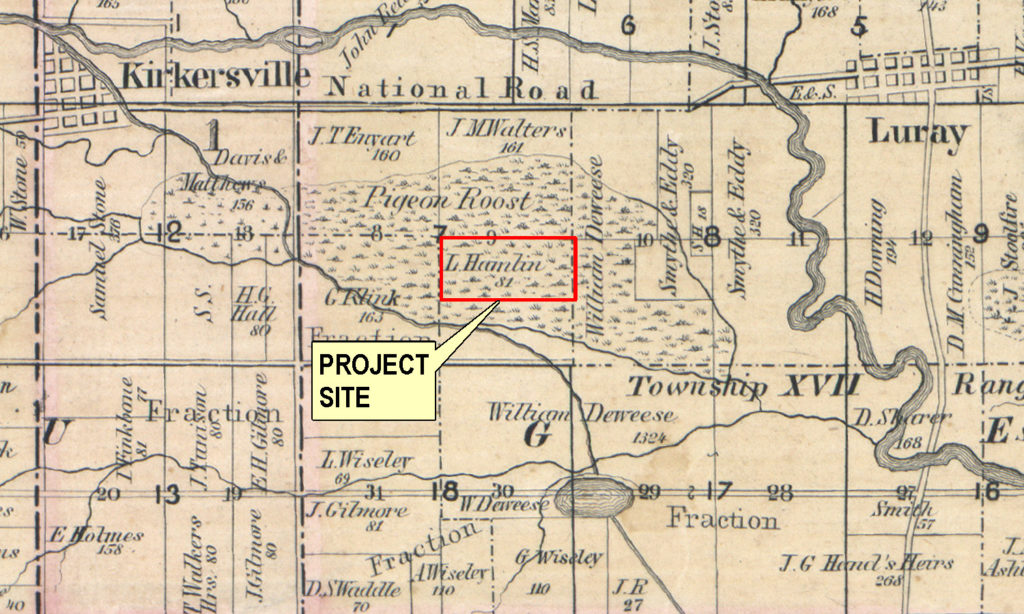

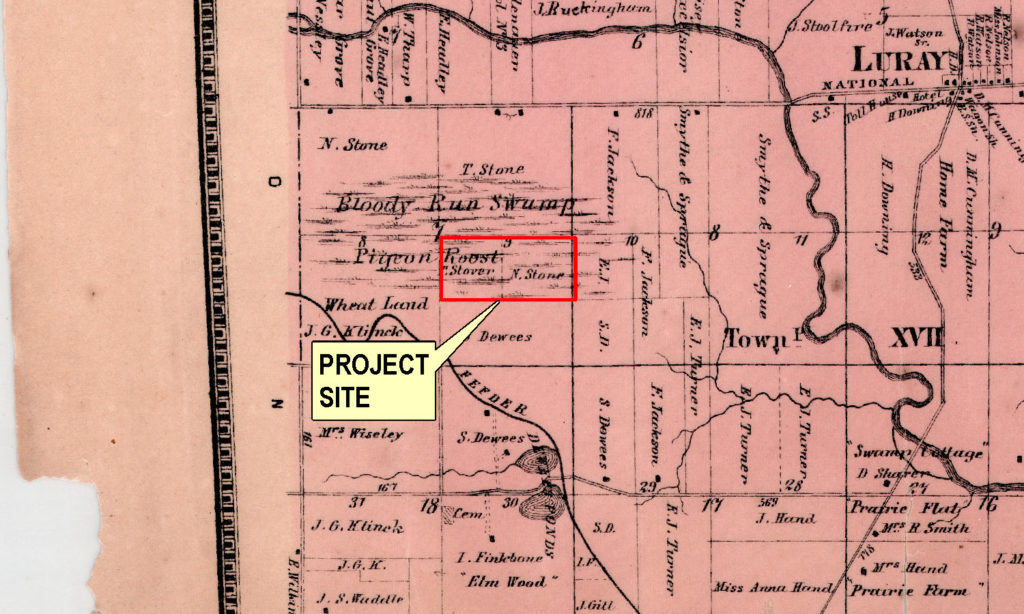

Figure 4 is the 1875 Union Township map, which labels the various islands located in the swamp. Sassafras Island and Long Island fall within the boundaries of this mitigation project.

In another description Schaff poetically wrote:

“When I was a boy three fourths of Etna Township was covered by a noble primeval forest. And now, as I recall the stately grandeur of the red and white oaks, many of them six feet and more in diameter, towering up royally fifty and sixty feet without a limb; the shellbark hickories and the glowing maples, both with tops far aloft; the mild and moss-covered ash trees, some of them four feet through; the elms and sturdy beeches, the great black walnuts and the ghostly-robed sycamores, huge in limb and body, along the creek bottoms, I consider it fortunate that I was reared among them and walked beneath them” (Schaff, 1905).

Other accounts describe the swamp as a “mixture of cranberry-sphagnum-red maple-poison sumac bog-swamps, alder-red ozier brush communities, and swamp forests of the elm-ash-soft maple-pin oak type” (Trautman, 1939). It was habitat for wild turkeys, blackbirds, beavers, bobcats, otters, timber wolves, black bear, white-tailed deer, raccoons, gray foxes, gray squirrels, muskrat, and passenger pigeons. At one time, Schaff wrote,

“There would be the appearance of a blue wave four-or five-feet high rolling toward you, produced by the pigeons in the rear flying to the front. When startled while feeding, their sudden rise would sound like rumbling thunder (…) Once they darkened the sky. Millions of them flew over Etna Township as they traveled to and from their feeding ground to roost in Bloody Run Swamp (Schaff, 1905).”

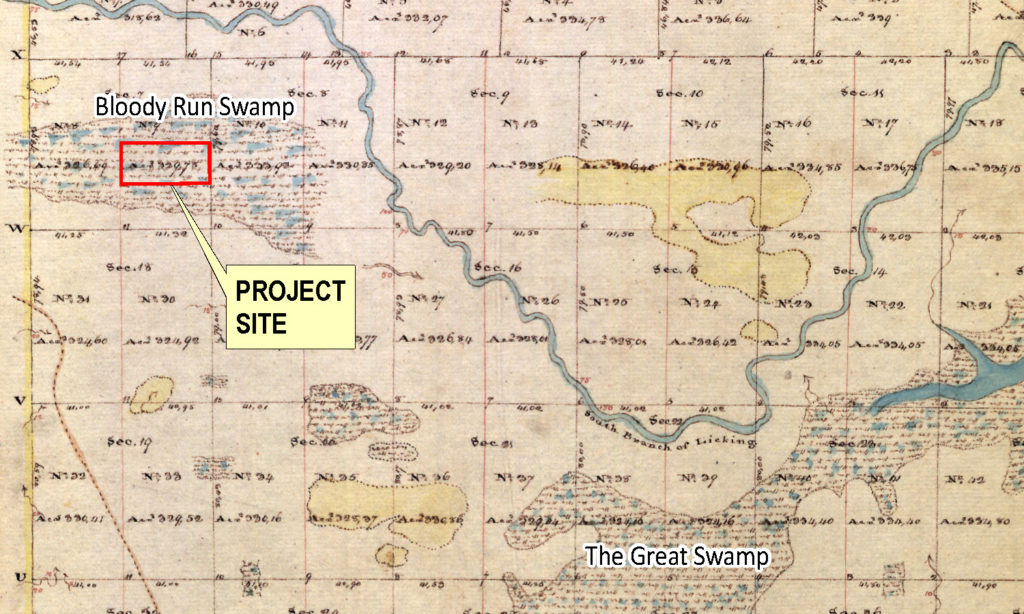

Figure 3 is another early map of the area showing the Pigeon Roost within the Bloody Run Swamp.

Transportation impacts to the area

In 1855, railroads became the third method of major transportation to the area. Greater accessibility allowed for an increase of markets for farm produce and other products. More forests were removed, and the first attempts were made at draining the Bloody Run Swamp. As livestock and crop cultivation became prevalent, many of the native animals became thought of as pests. Community hunts would take place where hunters would circle a given area and drive all the animals to the center. Once surrounded, all the animals would be shot. Competitive hunts also took place to reduce numbers of certain animals, such as gray squirrels. One such hunt in Licking County claimed 3,800 gray squirrels in a day (Trautman, 1939). The passenger pigeon was another species to be hunted in excess. Whereas, they were previously so abundant as to darken the sky, by 1880, they were almost completely gone from the area, eventually hunted to extinction.

Public Ditch Laws were enacted in Ohio during the 1840’s and 1850’s to encourage settlement in Northwest Ohio (ODNR 2009). Agricultural drainage improvement projects were enacted under those laws to facilitate the conversion of low-lying areas into productive agricultural lands across the state. Areas were quickly and systematically drained; by 1884 the Ohio Society of Engineers and Surveyors reported there were approximately 20,000 miles of public ditches benefiting 11 million acres of land (ODNR 2009).

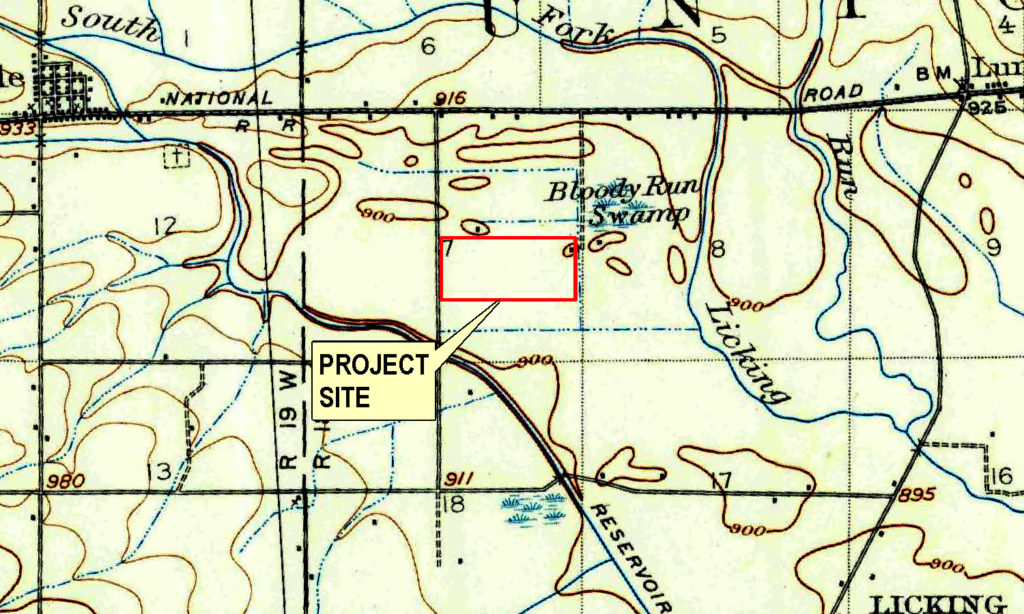

Between 1900 and 1930, the Bloody Run Swamp was completely drained and deforested, losing its distinctive flora and fauna. Schaff wrote in 1905, “The way that majestic forest was sacrificed is painful to recall.” Figure 5 is a 1906 USGS map that shows all but a small portion of Bloody Run Swamp was gone by that time. Records from 1912 indicate that it was almost wholly under cultivation at that time. Two farmers are mentioned as planting celery and onions in the rich muck soil (Detmers, 1912).

Restoring wetlands at this project, which was formerly part of the Bloody Run Swamp, will bring it back, as closely as possible, to its historical condition of centuries past. Very few mitigation sites have such rich history that includes detailed native species lists. This is an exciting opportunity to honor the past, while improving current water quality, sedimentation, and other ecological issues in the watershed. As Morris Schaff wrote, “Nature has many moods, but she was in her grandest when she ordered the woods of Ohio to rise up.”

Where we are today

The project is located within the Bell Run-South Fork Licking River watershed (HUC 05040006-04-06). The predominant land use within this watershed is row crop agriculture. This watershed drains some of the flattest, glaciated topography in the whole Licking River watershed (Ohio EPA, 2012).

Buckeye Lake, one of two lakes in this watershed, has cultural and recreation value to the area. The South Fork Licking River was modified to feed water to Buckeye Lake, where it then discharges back into the river. Based on nine yearly assessments, the lake is over-productive and impaired based on elevated dissolved oxygen, organic loading (N and P), and excessive Secchi depth values. The Biological and Water Quality Study of the Licking River and Selected Tributaries 2008 (Ohio EPA, 2012), put Buckeye Lake on a “watch” status, and it recommended preventing nutrient inputs into the lake. Wetlands perform many useful functions relating to water quality. Re-establishment of wetlands on the project will aid in improving water quality within the watershed; restoration activities will help reduce existing agricultural runoff that contributes to excess nutrients and sediment loading.

Population growth to bring environmental challenges

It is expected as the Columbus metro area grows, this will alter land uses in the entire Licking River sub-basin, particularly a decline in agriculture and increase in rural residences and mixed-use commercial/industrial areas. The MS4 program of Ohio EPA has currently listed the South Fork Licking River as a rapidly developing watershed. GROW Licking County Community Improvement Corporation estimates the Licking County population will increase by at least 15% over the next twenty years. There is evidence that land disturbance, such as construction activities, will increase stress on water quality, habitat, and aquatic life.

The agricultural drainage systems that were originally designed and maintained by county commissioners were primarily for water conveyance and management; they were not engineered as a water quality management tool. The channelized design of agricultural drainage ditches facilitated the conveyance of water but eliminated connectivity to an active floodplain resulting in the disruption of important hydrologic and geomorphic stream dynamics. The design also reduces nutrient assimilation and results in the increased transportation of sediment, nutrients, and other pollutants downstream, the majority of which are exported downstream by large storm events that take place <10% of the year (Davis 2015). Agricultural drainage systems promote algal production in sensitive ecosystems, like Buckeye Lake and Lake Erie, where eutrophication may result in periodic hypoxia and fish kills. Statewide monitoring work conducted by Ohio EPA has identified ditching and the channelization of larger streams as leading causes of impairment of water quality and the overall health of aquatic life (ODNR 2009).

In the Bell Run-South Fork Licking River sub-watershed, where the project is located, intensely farmed landscapes account for over one half of the area’s land use. Within the watershed, countless streams have been encapsulated in subsurface drain tile and approximately one third of the existing drainageways identified by the National Hydrology Dataset are impacted for agricultural benefit. The incised, over-wide trapezoidal channels are efficient at conveying base and flood flows. However, the lack of connectivity to an active floodplain interrupts important hydrologic and geomorphic dynamics required to maintain efficient water conveyance over time. The disruption of these dynamics results in the loss of stream power, and the ability to transport sediment through the system. Sediment accumulates throughout the channel, restricting the capacity of the entire drainage network. This necessitates routine maintenance to remove the accumulated sediments to maximize hydraulic capacity. However, dredging destabilizes bank slopes leading to additional erosion and scour and ultimately additional efforts to maintain channel function. This style of drainage network is costly, disrupts the existing ecology of the stream, and adversely impacts water quality (Fausey 1982). There is a critical need in these systems for innovative best management practices that improve ecosystem function while maintaining effective, low maintenance drainage.

Channel and floodplain restoration will significantly improve stream function and water quality. The primary goal of the project design is to reconnect Bloody Run to a restored forested floodplain to improve nutrient assimilation, reduce erosion and sedimentation, and improve water quality. Establishing an appropriate pattern, profile, and floodplain will increase flow capacity and reduce flooding during storm events. The improved hydrologic dynamics will also reduce maintenance needs within the drainage network allowing aquatic habitat to improve.

Map scans courtesy of BLM General Land Office Records, patent details, Ohio River Survey

1854 Wall Map of Licking County

Beers’ Atlas of Licking County 1866

Combination Atlas Map of Licking County Ohio, By L.H. Everts 1875

1907 USGS Thurston, Ohio